“Do you wear a snowsuit to keep warm in the winter? Or bring a backpack to school?” asks Science Center volunteer Ed O’Connor as a young girl stares up at the space suit replica in the Connecticut Science Center’s Space Gallery. “Well, this suit does the same thing for astronauts; it has everything to keep you alive.”

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, I sat down with former engineer and current Science Center volunteer Ed O’Connor to talk about his experience as an inventor/engineer and the history of Connecticut’s longtime involvement in the space program. As children explored the activities in the Space Gallery, Ed and I sat in front of the space suit replica and talked about his involvement in developing the technology used on the Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, I sat down with former engineer and current Science Center volunteer Ed O’Connor to talk about his experience as an inventor/engineer and the history of Connecticut’s longtime involvement in the space program. As children explored the activities in the Space Gallery, Ed and I sat in front of the space suit replica and talked about his involvement in developing the technology used on the Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

Ed O’Connor has spent 48 years of his life working on the space program. After graduating with a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Manhattan College in 1963 and a M.S. in mechanical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1964, Ed went to work at the Hamilton Standard division of United Technologies Corporation (UTC)—then known as Hamilton Sundstrand and now a part of Collins Aerospace—in Windsor Locks, CT. He started on a project group working on the Lunar Module writing specifications, fitting for tube connectors, and developing plans to test equipment.

The Apollo 11 spacecraft itself consisted of three parts: The Command Module, Columbia, which housed the astronauts during their mission; the Service Module, which provided storage for resources such as oxygen, water, electric power, and jet propulsion; and the Lunar Module, Eagle, which carried the astronauts to land on the moon.

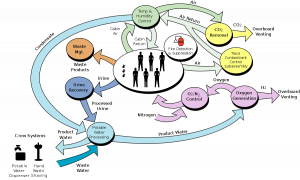

To construct the Lunar Module, Grumman was hired as the primary contractor, with four major subcontractors: TRW’s Space Technology Laboratories (to build the descent engine that descended onto the moon), Bell Aerosystems (to build the ascent engine that took the astronauts back to earth), Marquardt (to develop the reaction control system), and Hamilton Standard (to construct the environmental control systems). The Lunar Module’s environmental control system performed eight functions: it provided oxygen for the astronauts to breathe in their suits and in the spaceship; provided ventilation to warm or cool the astronauts; removed carbon dioxide waste to recirculate and reuse oxygen; cooled down electronic equipment within the LM vehicle; let out all heat waste into deep space; provided water for drinking and food preparation; and contained enough oxygen and water to support the portable life support systems for the duration of the astronauts’ time in space.

When looking back on the moon landing on July 20, 1969, Ed remembers the moment fondly. He recalls watching the news on TV at home after sending his young children to bed that evening. “One of the things you’re concerned about and you’re hoping for is that your equipment works and doesn’t break. That pressure is always there; there is still the knowledge of what can go wrong with those parts. At the same time, I had the confidence of how we tested it because the specs that we tested it to were far more severe than anything they would encounter. So that way, if they could stand the more severe environment, they were certainly going to be okay in the more limited environment that they were going into.”

Additionally, Ed vividly recalls the worry that he and others felt while watching the Lunar Module touch down on the moon’s surface for the first time: how solid is the lunar surface? “There always was a concern that as they landed, they were going to end up landing on a soft spot. And if that had happened then they would start tilting. And that’s why they had two stages of the lunar module, including the descent stage, which then became a platform. It’s the landing stage of the vehicle on top of it.”

Of course, the Lunar Module landed safely on the moon and Neil Armstrong took his famous first steps. Ed remembers that Armstrong’s iconic statement surprised him: “He said basically one small step for man, one great step for mankind. But I never expected anything so poetic and really something that would last forever, as a statement forever.”

As part of the Hamilton Standard team that would continue to build and improve the life support systems after that momentous occasion in 1969, the challenge for Ed and the team was to develop a way to reuse and recycle resources on the space stations and inside the astronauts’ suits. For example, the Lunar Module was an open-loop system (or a throw away system). This means that waste was largely thrown out into space after use, given that it was making a relatively short journey. Ed’s new challenge was to provide life support systems for astronauts staying in space for longer missions, such as on the International Space Station or the portable life support system (PLSS). For these types of scenarios a closed-loop system (or a regenerable system) that recaptures and reuses resources, is more appropriate. Ed explains, “In a closed-loop system, instead of having an oxygen tank, what you will have is an electrolysis process. Now if you remember H₂O, water, that provides H₂ and O₂, that’s where the oxygen comes from. You feed that into an electrolysis process and that provides the oxygen—that’s going to go to the man. He’s going to consume the oxygen and he’s going to make water again. So we recover that water in the water processor so we can feed the electrolysis system again and provide whatever water he needs.” This water processor system, which was launched in 2008, has since recycled 8,000 pounds of water per year.

Over the course of Ed’s career, he invented many different technologies that have changed the way humans can survive in space, such as the Slurper and the Water Spray Boiler. “The Slurper is a first-stage humidity condensate separation device that removes water vapor collected from the astronauts and recycles it for other use. The Slurper is used on the Space Shuttle Orbiter, Spacelab, International Space Station, and Extravehicular Mobility Unit (space suit). The Water Spray Boiler, which has flown on shuttle missions, satisfies the need for zero gravity evaporative cooling of high pressure hydraulic fluid, as the spacecraft engine is launching during liftoff.

From the moment that John F. Kennedy promised the nation in 1961 that we would reach the moon within the decade, it was clear that many teams of people were needed to make that promise a reality. Since then, Connecticut has had a long history of partnership with the space program that continues to this day. Since Hamilton Standard was awarded the contract to develop the lunar module environmental control systems, Ed says that was the beginning of a “technical odyssey, continuing up to the present date, that included Manned Orbiting Research Laboratory, Biosatellite, the USAF’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory, NASA’s Space Station Prototype, Skylab, Space Shuttle, Space Station Freedom, International Space Station, Orion, and Commercial Space Transports. Connecticut was a strong contributor to the Lunar Program and, as a consequence, was well-rewarded with recognition and with many, many good jobs for a number of years.”

Since Ed’s retirement in 2011, he has been a volunteer at the Connecticut Science Center, where he helps kids in the exhibit galleries, “What I enjoy most is working in the Forces in Motion Gallery, where I teach the kids how to make paper airplanes, because that’s where kids tend to go to be active, and I enjoy that. I looked forward to being involved [in the Science Center]. I wanted to pay back and not just teach children about science, but also make kids feel good about themselves, and what they can do. Because in science and in your own life, you’ve got to learn how to think outside the box, and I give them the means to do that. You can see that they’re learning.”

Since Ed’s retirement in 2011, he has been a volunteer at the Connecticut Science Center, where he helps kids in the exhibit galleries, “What I enjoy most is working in the Forces in Motion Gallery, where I teach the kids how to make paper airplanes, because that’s where kids tend to go to be active, and I enjoy that. I looked forward to being involved [in the Science Center]. I wanted to pay back and not just teach children about science, but also make kids feel good about themselves, and what they can do. Because in science and in your own life, you’ve got to learn how to think outside the box, and I give them the means to do that. You can see that they’re learning.”

On Tuesday, July 16, Ed O’Connor was honored at the Connecticut Science Center’s press event for the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 launch, as we revealed the Connecticut State Flag that flew in space on the Space Shuttle Atlantis and in the International Space Station (ISS) in 2000. The flag was donated to the Connecticut Science Center by Connecticut native and astronaut Captain Dan Burbank. The space-flown flag joins a lunar sample—a basalt rock fragment on loan from NASA from the Apollo 15 mission—on display in the permanent Exploring Space Gallery, presented by United Technologies. Hands-on activities in the gallery include a Lunar Lander simulation for young children and a space pod galaxy simulation, along with educational and hands-on features on rocketry, crater making, and lunar topography. A copy of the 200+ page “press kit” developed by NASA for media covering the Apollo 11 mission in 1969 can also be seen, along with a replica Apollo-era space suit.

Come join us at the Connecticut Science Center on Saturday, July 20, to celebrate the historic lunar landing while watching Jungle Jim’s space-themed balloon animal show, listening to 60s music performed by CJ West and the Downtown Train, and watching the newly released cinematic masterpiece Apollo 11: First Steps Edition (playing throughout the summer, but on July 20 visitors can see it for only $1.50 – the same price as a movie ticket in 1969). Apollo 11 programming is supported by the NASA Connecticut Space Grant Consortium.

Acknowledgements: Thank you Ed O’Connor for his life’s work contributing to the space program and for the honor of letting me interview him. A huge thanks to Jacqueline Moore for filming and video editing, and Katrina McGlynn for sound and set-up.

Amanda Coletti is a Communications Research Assistant at the Connecticut Science Center and a Ph.D. student in the Department of Communication at the University of Connecticut, where she studies the science behind science communication.