As you enter the lobby of the Connecticut Science Center you’re greeted by a massive sail-backed dinosaur with a crocodile’s snout. This is Spinosaurus, one of dozen animatronic prehistoric creatures showcased in our new exhibit Dinosaurs Around the World: Passport to Pangea.

As you enter the lobby of the Connecticut Science Center you’re greeted by a massive sail-backed dinosaur with a crocodile’s snout. This is Spinosaurus, one of dozen animatronic prehistoric creatures showcased in our new exhibit Dinosaurs Around the World: Passport to Pangea.

At over 50 feet long, Spinosaurus was one of the largest predatory dinosaurs known- even larger than Tyrannosaurus rex. It was discovered in 1912 during a fossil dig in Egypt led by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer.

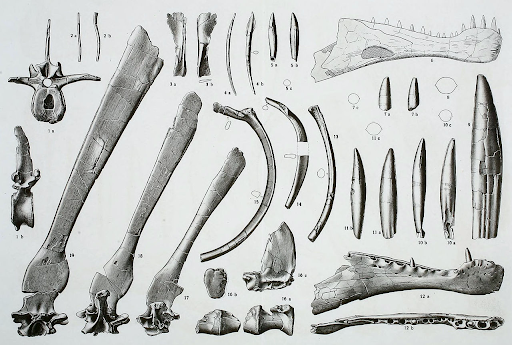

Sadly the original Spinosaurus fossil was destroyed when the Munich museum it was housed in was bombed during World War II. For decades our only knowledge of Spinosaurus came from the notes and drawings Stromer had made. But these drawings were detailed enough for paleontologists to form a few theories about Spinosaurus. They observed that the dinosuar’s jaws- and those of its close relatives Baryonyx and Suchomimus- looked remarkably like those of a crocodile. Spinosaurus and its cousins also had conical teeth and large hooked claws which would have been perfect for snagging slippery prey. These features indicated that Spinosaurus was likely a fish-eater, which makes sense since Egypt in the Late Cretaceous, when Spinosaurus lived, was a tropical estuary full of mangrove-lined rivers full of sharks, lungfish, coelacanths, and other giant fish.

Over the decades more and more fossil fragments of Spinosaurus have been discovered in Northern Africa, allowing researchers to learn more about its appearance and lifestyle.

For example, studies of oxygen and calcium isotopes in Spinosaurus bones and teeth showed that these dinosaurs spent a large amount of time in the water hunting for fish and other freshwater animals. At the same time, a comparison of Spinosaurus’ snout to the elongated noses of several modern crocodile and alligator species suggested that, though it primarily hunted in rivers, it was not exclusively a fish eater and may have also sometimes preyed on land animals as well.

For example, studies of oxygen and calcium isotopes in Spinosaurus bones and teeth showed that these dinosaurs spent a large amount of time in the water hunting for fish and other freshwater animals. At the same time, a comparison of Spinosaurus’ snout to the elongated noses of several modern crocodile and alligator species suggested that, though it primarily hunted in rivers, it was not exclusively a fish eater and may have also sometimes preyed on land animals as well.

The discovery of several nearly complete Spinosaurus fossils in 2014 showed multiple adaptations to a semi-aquatic lifestyle. It had an elongated neck and torso that shifted its center of mass away from its back legs and towards the middle of its body, allowing it to lie flat in the water like an alligator without tipping backwards. Its nostrils were also pushed farther back on its snout in a position where they would have been high above the water line if the creature floated horizontally.

Spinosaurus’ bones were solid, unlike the bones of many other dinosaurs which were hollow and bird-like. Thick bones are also found in penguins and other aquatic animals and allow them to control their buoyancy.

Studies on the tip of Spinosaurus’ snout indicated that it was packed with a network of highly-sensitive nerves which could have been used to detect moving prey in murky water. Modern alligators and crocodiles possess similar snout-nerves.

Paleontologists have also found that Spinosaurus teeth were far more abundant in riverbed sediments than those of any other dinosaur from Cretaceous Egypt.

In 2020 paleontologists discovered a Spinosaurus tail for the first time and found that it was vertically-flattened like an eel’s and would have enabled the dinosaur to paddle swiftly through the water in pursuit of prey.

All these discoveries make it clear that Spinosaurus was well-adapted to live and hunt in the rivers of its homeland, but exactly how much time it spent in the water is still debated. Some researchers have speculated that it might have been almost fully aquatic, able to dive after prey and use its sail for stability much like the sail of a swordfish or the tail of a thresher shark. Recent studies, however, indicate that Spinosaurus might have been more of a shallow-water wader, probing the surface with its snout and snatching up prey like a gigantic stork or grizzly bear.

All these discoveries make it clear that Spinosaurus was well-adapted to live and hunt in the rivers of its homeland, but exactly how much time it spent in the water is still debated. Some researchers have speculated that it might have been almost fully aquatic, able to dive after prey and use its sail for stability much like the sail of a swordfish or the tail of a thresher shark. Recent studies, however, indicate that Spinosaurus might have been more of a shallow-water wader, probing the surface with its snout and snatching up prey like a gigantic stork or grizzly bear.

Our interpretations of dinosaurs are constantly changing as paleontologists dig up new fossils and make new discoveries. Come see Dinosaurs Around the World and form your own ideas about how these prehistoric creatures looked and lived.

Dinosaurs Around the World: Passport to Pangea is now open at the Connecticut Science Center and is included with General Admission. Visit CTScienceCenter.org to reserve your ticket online in advance of your visit.

John Meszaros is a Visitor Services Specialist at the Connecticut Science Center. He has a degree in Biology from the University of Michigan. John has a strong interest in biology, astronomy, oceanography, geology and other natural sciences. He is an avid writer and illustrator who enjoys sharing his love of the natural world with others.