At the Connecticut Science Center, you can learn a lot about the moon. You can find out how its craters were formed-and make some yourself. You can see where humans landed on its surface and follow the history of lunar exploration. Your kids can even play in a miniature lunar lander.

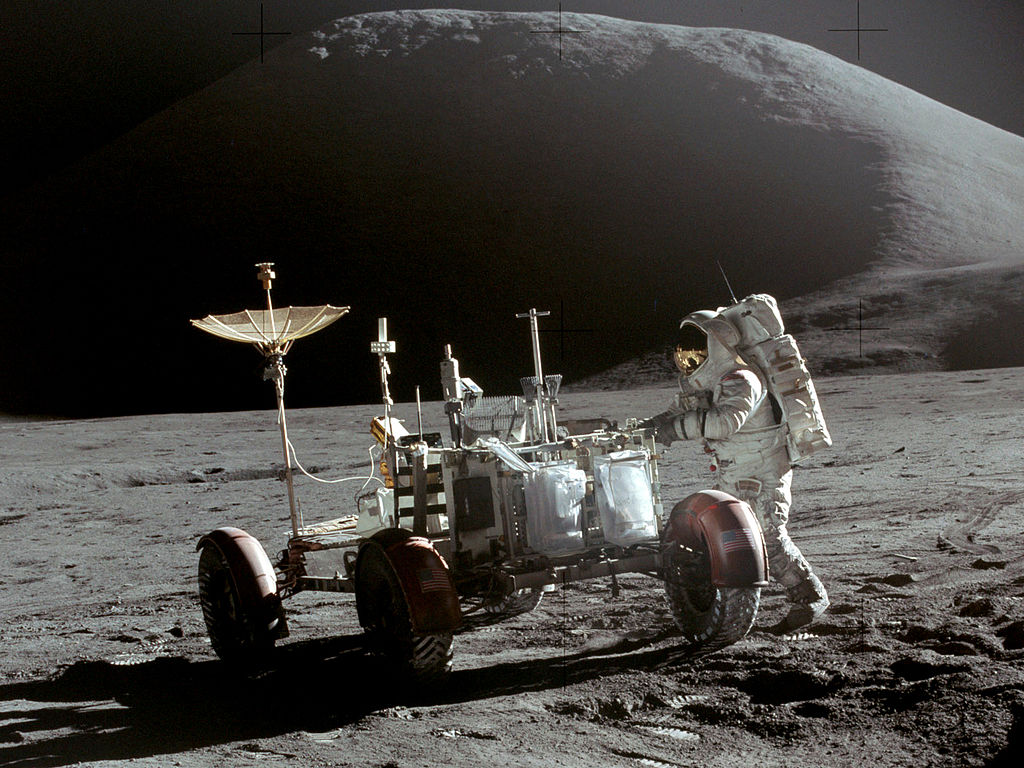

But did you know you can see an actual piece of the moon up close right here at the Connecticut Science Center? Located in the Space gallery next to our replica Apollo 11 astronaut suit is a humble-looking chunk of rock carefully sealed in a thick acrylic cylinder. While it may look like any stone you could find on a walking trail in the woods, this particular stone has come a long, long way. This is a piece of “Great Scott”, one of the largest and most extensively studied lunar samples brought back to Earth. “Great Scott” was collected in 1971 by the crew of Apollo 15, the first of NASA’s “J series missions, which were designed to allow astronauts to remain on the moon for a longer period of time than other missions. Apollo 15 was also the first mission to use the Lunar Roving Vehicle, or LRV, to explore farther from the landing site than previous missions had been able.

But did you know you can see an actual piece of the moon up close right here at the Connecticut Science Center? Located in the Space gallery next to our replica Apollo 11 astronaut suit is a humble-looking chunk of rock carefully sealed in a thick acrylic cylinder. While it may look like any stone you could find on a walking trail in the woods, this particular stone has come a long, long way. This is a piece of “Great Scott”, one of the largest and most extensively studied lunar samples brought back to Earth. “Great Scott” was collected in 1971 by the crew of Apollo 15, the first of NASA’s “J series missions, which were designed to allow astronauts to remain on the moon for a longer period of time than other missions. Apollo 15 was also the first mission to use the Lunar Roving Vehicle, or LRV, to explore farther from the landing site than previous missions had been able.

The Apollo 15 lander touched down in a region between a collapsed lava tube called Hadley Rille, and the Apennine Mountains, which are actually the eroded rim of a massive ancient impact crater. NASA chose this site to allow astronauts to explore the most ancient lunar terrain, represented by the mountains, and the geologically younger terrain of the volcanic rille.

Apollo 15 was crewed by command module pilot Alfred Worden, lunar module pilot James Irwin, and commander David Scott, after whom “Great Scott” is named.

The piece of “Great Scott” owned by the Connecticut Science Center is composed of basalt, a mineral formed from cooled lava. Basalt is a quite common mineral on both the moon and Earth. In fact, most of the mountain-like ridges that run through Connecticut’s Central Valley are made of basalt.

“Great Scott”, however, is much, much older than Earthly basalts, having formed approximately 3.3 billion years ago when the moon was still very young. Rocks on Earth are rarely this old because erosion and plate tectonics are constantly breaking down and reforming them. The moon, however, has no tectonic plates and no wind or water. The only alterations to its surface come from meteor strikes, which do break the surface into rubble and dust, but otherwise leave the minerals within the rock relatively intact. Thus, the majority of lunar rocks have existed in their current state since the moon’s formation.

When the kids are out of school, don’t panic – just plan a safe, fun adventure to the Connecticut Science Center! You can explore four floors of fun with more than 165 interactive exhibits, including our Space Gallery on Level 5. Reserve tickets online before your visit on CTScienceCenter.org

John Meszaros is a Visitor Services Specialist at the Connecticut Science Center. He has a degree in Biology from the University of Michigan. John has a strong interest in biology, astronomy, oceanography, geology and other natural sciences. He is an avid writer and illustrator who enjoys sharing his love of the natural world with others.