What is this so-called physiological stress response? What is actually happening in our brains and in our bodies? Our story begins with a stressor, or some event or experience we perceive as a threat. Imagine you are standing on a sidewalk and hear the sudden blare of a car horn. Looking up, you see a car quickly coming down the road, heading toward you. Can you feel your heartbeat quickening just thinking about it? You aren’t even in the situation and your stress response is already getting ready for action.

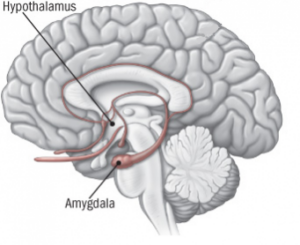

At the initial threat of danger (the sound of the car horn and sight of the car) our eyes and ears send information to the amygdala, a structure deep in the brain about the size and shape of an almond that plays a major role in our stress response. The amygdala processes the images and sounds and essentially lights the bat signal, or should I say hypothalamus signal.

At the initial threat of danger (the sound of the car horn and sight of the car) our eyes and ears send information to the amygdala, a structure deep in the brain about the size and shape of an almond that plays a major role in our stress response. The amygdala processes the images and sounds and essentially lights the bat signal, or should I say hypothalamus signal.

Once the amygdala sends out a distress signal to the hypothalamus, it can take over as control center. The hypothalamus, sometimes referred to as our thermostat, essentially maintains stability in our bodies. It is also the link between our nervous system and our endocrine system. The endocrine system is our chemical communication system that uses hormones as messengers. Assuming command, the hypothalamus calls the rest of the body to action through the autonomic nervous system, which controls bodily functions we don’t consciously think about, such as breathing, blood pressure, and our heartbeat.

The autonomic nervous system has two parts – the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. Keeping with our car analogy, think of the sympathetic nervous system as your stress response’s gas pedal, while the parasympathetic nervous system is the brake. We are going to focus on the sympathetic nervous system because right now, there is no time for the brake! We are all systems go!

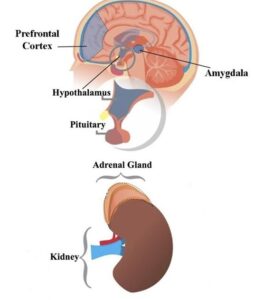

The sympathetic nervous system triggers the famous “fight or flight,” also known as the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. It prepares you for action, whether it be to fight off a threat, or to get yourself to safety. Signals are sent to the adrenal glands, small structures sitting atop our kidneys, and a hormonal flash flood ensues. The adrenal glands release the hormone adrenaline into the bloodstream. All the while, the hypothalamus is still hard at work activating the next wave, the HPA axis (hypothalamus, pituitary gland, adrenal gland). This essentially keeps the gas pedal of our stress response pressed down, ultimately causing the adrenal glands to release another stress hormone, cortisol.

Adrenaline and cortisol cause a number of changes in our body. Imagine you are back on that sidewalk. Your heart begins beating faster than normal, pushing blood to your muscles and vital organs. Your blood pressure increases. Your palms begin to sweat. You’re breathing more rapidly and passageways in your lungs are opening wide so your lungs can take in as much oxygen as possible with each and every breath. Extra oxygen is heading to your brain. Suddenly, you feel more alert and your senses become sharper. Sugar (glucose) and fats are released from temporary storage sites in your body, supplying you with a burst of energy. You start to feel butterflies in your stomach as your digestive system slows down, allowing your body to focus on what is most important in the moment – your safety.

The amazing part of this process (which should make you feel like the superhero that you are) is its SPEED. This is all happening even before your brain has had a chance to fully process the situation. Trust me, you want it to happen quickly. If the danger is real, we want to be ready for it without thinking. We want to be able to jump out of the way of the moving car without having to weigh the pros and cons. But, even though our body is evolutionarily built to protect us from threats, it isn’t always the best at knowing what a “real” threat is. The amygdala doesn’t really know the difference between a fiery blaze and a piece of charred toast sitting in the toaster. That’s where your prefrontal cortex comes in.

As your stress response is keeping your engine revved and ready for action, the prefrontal cortex, an essential part of the brain just behind your forehead, is evaluating the information at hand. Though it may take longer, it decides what to do and sends messages to the amygdala to stand down when a threat has passed, or in the case of the charred toast, when there isn’t a threat at all. Then, the parasympathetic nervous system, or the brake, can finally take action. In the case of the car honking and driving toward you, it was actually a friend stopping over to say hello! Your parasympathetic nervous system can now activate your “rest and digest” response to help your body get back to normal.

So this is all great, right? We are superheroes, complete with a built-in evolutionary adaptation designed to keep us safe! Well, yes and no. While our stress response protects us, just like cars, we weren’t designed to keep the gas pedals pressed down all the time. Given all of the everyday stressors we are exposed to, that can very easily happen. Studies have shown that stress can affect our attention and memory. In a stressful situation, the amygdala can sort of take over, and the brain diverts its energy to where it is needed most. According to Dr. Kerry Ressler, chief scientific officer at McLean Hospital and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, the brain essentially goes into survival mode, not memory mode. That can make it hard to focus on anything other than the stress. This is part of the reason why we can’t just think our way out of stress. Also, anxiety is in the mind AND the body, so it isn’t so simple to just eliminate it. Cortisol released during our stress response also suppresses the immune system, making us less able to fight off illness. Muscle tension increases, which can cause or worsen pain and migraines. Since our digestive system is less active during stress, that can lead to some unpleasant effects, like bloating, nausea, or diarrhea. Long-term stress can also damage our blood vessels and arteries, which can increase the risk for heart problems. The list goes on and on.

Once again, we will go into a lot of different strategies in these posts that can help with mild anxiety, but if you find your anxiety doesn’t respond to these types of techniques, or affects your daily functioning or mood, explore talking to a mental health professional. They will be able to examine your own individual experiences and provide tools and strategies to help. A psychologist can also help to determine whether you have an anxiety disorder. While I am not qualified to make any such diagnoses, I can once more assure you that you would NOT be alone. According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, “anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the U.S., affecting 40 million adults”, or 18.1% of the U.S. population every year. Looking over a lifetime, the National Institute of Mental Health found that an estimated 31.1% of U.S. adults experience an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO), states that 1 in 13 suffers from anxiety disorders.

Are we just slaves to our stress? Are we unable to avoid this growing list of side effects? NO! We can actually use our biology to our advantage! Stay tuned for our final “Science of Stress” post, where we will dive into science-based strategies to help manage stress and anxiety.

Want more? Check out our full Science of Stress series

Read the Science of Stress: Realizing We Are Not Alone

Read the Science of Stress: Helpful Strategies

Stay connected! Be sure to subscribe to Down to a Science— The Official Blog of the Connecticut Science Center and follow us on social media.