Inconspicuous Consumption author Tatiana Schlossberg

Author Tatiana Schlossberg asserts that “our daily activities don’t exist in a vacuum,” and spends the next 236 pages of Inconspicuous Consumption digging into minutiae like the role athleisure plays in microplastic fibers entering our waterways. This is the product of a journalist who asks question after question. She investigates everything from how we are “exporting our emissions by growing food in Mexico” and importing it, to the toxicity of Silicon Valley.

She uses a chatty, self-deprecating tone to connect with the reader — a technique that I found hit or miss. What was more engaging was her choice of topics. Can you get more American than apples and blue jeans?

The author describes her love of the apples from Rogers Orchards in Southington, Connecticut. When she is in the area to visit family, she drops in. She admits to having indulged in having them shipped when she could not make the trip, explaining how she “ordered some online at great personal expense. I maintain that the cost was worth it.” This detail about the author’s own consumption habits sticks with the reader, though the point she is making here is about the trickiness of food labels — something that Michael Pollan covered extensively in his 2006 book The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Her beloved apple provider uses integrated pest management, a system the EPA considers environmentally sensitive, though products grown this way cannot wear the “USDA organic” badge.

Later, Schlossberg tries to get to the bottom of denim, explaining that “talking about jeans is, principally, a way to talk about cotton.” Most people know that cotton is a water-intensive crop, but having that scrap of knowledge is not the same as being able to quantify it or think of what happens after it is harvested. The author tells us that “as much as 2,900 gallons [of water] can be used to produce a single pair of pants (using conventional methods), mostly because of the dyeing and finishing.” Instead of hinting that consumers might reduce the rate at which we purchase jeans, or opt for second-hand suppliers, she stops at her research into how some manufacturers are reducing their impact. Levi’s Water<Less program, she shares, “by their accounting, [saved] more than 525 million gallons of water and recycled another 52 million gallons.”

As she writes, “it’s not really about using a plastic bottle or not using a plastic bottle (don’t think I’m letting you off the hook for your personal habits, though: we used more than 56 billion plastic bottles in the US in 2018 and we mostly don’t need to), or sipping from a paper straw or a plastic one. It’s much bigger than those things. It’s a global problem in the most literal meaning of the word.” Buried in the footnotes, she expands on this: “most of us don’t need straws, and yes, the plastic pollution caused by straws is bad for the environment. […] It might be time to reconsider take-out and our ‘on-the-go’ culture instead.” This throwaway remark in tiny print deserved to be expanded into its own chapter.

It does not feel as if Schlossberg holds the reader accountable for our bad habits, and a number of her threads dissolve into ambiguity, but she does amp up her content in the last section of the book, where she finally addresses fossil fuels, “arguably the most important problem to solve.” Why did it take so long? She thinks the reader would have stopped reading if it were discussed in the first chapters because “the way that we talk and write about it is pretty technical and abstract and, therefore, often kind of boring.” To be honest, as I read, I wondered why she got deep into the production of cashmere but had not scratched the surface of transportation impacts. Had I not previewed the table of contents, I may have given up. Her sugary writing style may appeal to some, but I found it excessive and distracting. At times, it worked to minimize the seriousness of the topic, which did not seem to be her intent. What I did not love about the book is exactly what might have more appeal to others — an author who seems non-judgemental and friendly, and who eases the reader into the subject matter. Regardless, the conclusion is solid, and overall, this is a worthwhile read for those who like to collect facts about “everything we use: what it’s made of, how it’s made, how we use it, what happens when we throw it away.”

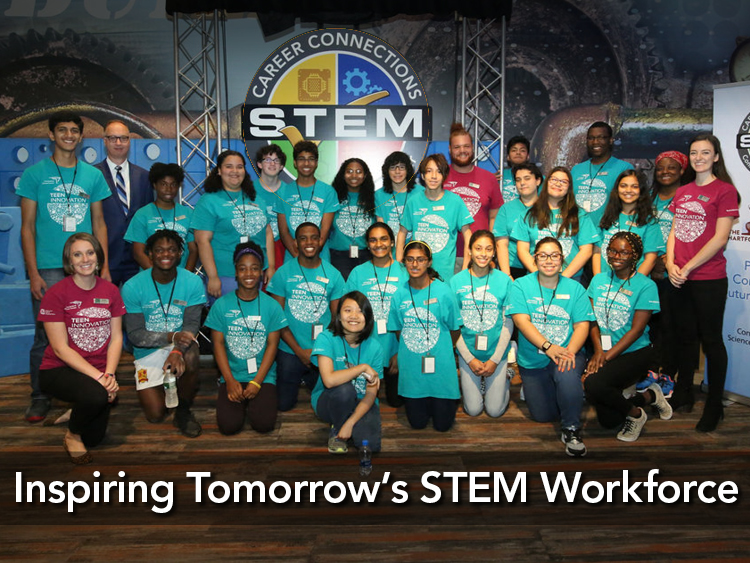

Interested in knowing more about your impact? Stop by the Connecticut Science Center’s “Energy City” exhibit.

Kerri Provost is a Communications Research Associate at the Connecticut Science Center who is outdoors whenever possible and is currently attempting to walk every block of Hartford. She is the co-producer of Going/Steady , a podcast about exploring in the Land of Steady Habits and beyond.