Hurricane Maria, 20 September 2017 / Image courtesy of NASA

Before the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service began air-dropping food in Yengo National Park and other sites ravaged by fire, prompting viral videos of adorable Brush-tailed Rock-wallabies munching carrots, we were inundated with weeks-upon-weeks of horrifying images: scorched earth and charred wildlife carcasses.

Although I have never stepped foot on Australia, I have good friends living there who happened to be visiting Kangaroo Island when lightning strikes set off the island’s second bushfire. It’s harder to ignore the news cycle when you are only a few degrees of separation from a region. As upsetting, though, as these events and images have been, I am fortunate to not be experiencing the fires directly, nor do I have PTSD from any other natural disaster.

Others are not as lucky. As the Guardian reports, a 1991 study “found that as many as 40% of those directly affected by climate-enhanced superstorms and fires suffer acute negative mental health effects, some of which become chronic.” Six months after Hurricane Sandy, 14.5% of Monmouth County (New Jersey) adult residents screened positive for PTSD. Those impacted by disasters range from children to emergency service workers to adult civilians. As droughts and tropical storms intensify, we need to think about how climate change is impacting the mental health of humans.

While children are more resilient than adults, “[c]hildren often see traumatic events as punishment for misbehavior, ascribe unrelated causality, have difficulty discussing the event because of limited language skills and have poorer abstract reasoning skills which impacts their comprehension.” To reduce anxiety in children who fear storms, Mayo Clinic suggests parents share factual information about the causes of weather events, while talking to them about the family’s plan to stay safe. University of Michigan recommends using honesty when discussing an event with children, but not sharing more information than the child has asked for. Limiting media exposure is also important; don’t let youth watch news clips over and over, as young children may believe that the looped video is an ongoing event. For those being impacted directly, it’s advised that people stick to routines as much as possible — especially those who have children. After, if possible, try to do something positive, like donate blood, to help others.

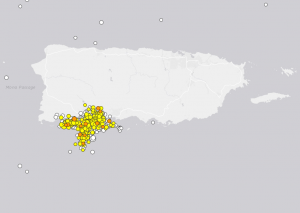

This shows earthquakes with a magnitude 2.5+ impacting Puerto Rico from December 23, 2019 through January 22, 2020. // Image courtesy of USGS.gov

Connecticut is not as vulnerable to weather and climate disasters as other states, yet this remains relevant. We have already received climate migrants and refugees. Following Hurricane Maria, over 13,000 Puerto Ricans were displaced to our state. Many returned to Puerto Rico or moved to other states since, but some remain here, with family and friends on an island that has experienced a series of earthquakes in the Ponce and Guánica region, beginning at the end of December 2019, continuing for weeks. On the island, people are sleeping outside because aftershocks have been predicted and there are worries that homes will crumble on them while they sleep. Several government structures have been ordered closed while waiting for inspection by engineers. Punta Ventana, a landmark, has collapsed. The Red Cross is providing mental health services for those in Puerto Rico, many of whom, as they say, “are still working to recover from 2017’s devastating hurricanes.”

Adults who have experienced trauma can be re-traumatized, essentially reliving previous events. California wildfire survivors, for instance, have been triggered by subsequent fires.

If we need to find a silver lining, it’s that as a whole, our society has gotten better at acknowledging and identifying trauma, and the general need for psychological first aid in the midst of disaster. The University of Houston, for example, shared resources with its college community following Hurricane Harvey, explaining various symptoms (panic attacks, sleep disturbances, extreme distress, and more) that might indicate a person who would benefit from counseling and support. It is hopeful that a portion of the Australian government’s promised $2 billion for recovery following the fires will be used for ongoing, long-term mental health treatment for residents.

For those wanting to learn more about:

- stress and stress management during natural disasters, see the resources compiled by SAMSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

- helping the Puerto Rico earthquake relief effort, connect with the Hispanic Federation

- emergency preparedness and first responders, visit the Connecticut Science Center’s “Our Changing Earth” exhibit.

Kerri Provost is a Communications Research Associate at the Connecticut Science Center who is outdoors whenever possible and is currently attempting to walk every block of Hartford. Because the world is endlessly interesting and amazing, Kerri enjoys taking a multidisciplinary approach, making connections between science, history, and more. She is the co-producer of Going/Steady , a podcast about solo travel in the Land of Steady Habits and beyond.