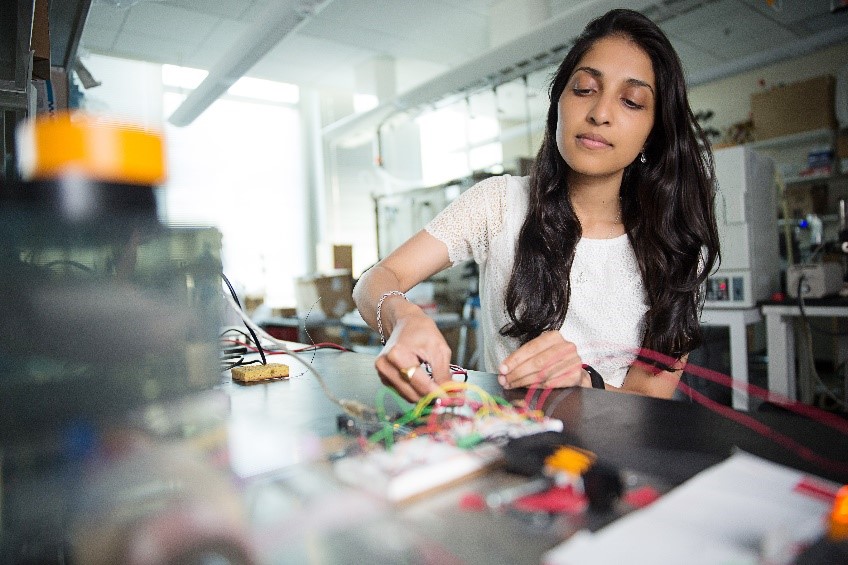

This summer, I interned with the Connecticut Science Center’s Programs team through the NASA Connecticut Space Grant Consortium. I wanted to use my passion for 3D designing, engineering, and STEM education to give back to the community. While writing a blog post on mechanical engineering and robotics, I came across Dr. Ritu Raman, an assistant professor at MIT in the IF/THEN® Collection. I was eager to learn more about her fascinating work, so I reached out to see if she might be interested in sharing more about her career and her current project, biohybrid robots. These tiny little inventions can change the world of robotics as we know it.

Dr. Raman is starting her first year as a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) after completing four years of postdoctoral work. As part of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, she will lead a research lab and teach undergraduate students an introductory Mechanics of Materials course. Remembering how challenging the first year of college can be, Dr. Raman shared that she is excited about this course and will be glad to check in and see how much she has learned.

Dr. Raman is starting her first year as a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) after completing four years of postdoctoral work. As part of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, she will lead a research lab and teach undergraduate students an introductory Mechanics of Materials course. Remembering how challenging the first year of college can be, Dr. Raman shared that she is excited about this course and will be glad to check in and see how much she has learned.

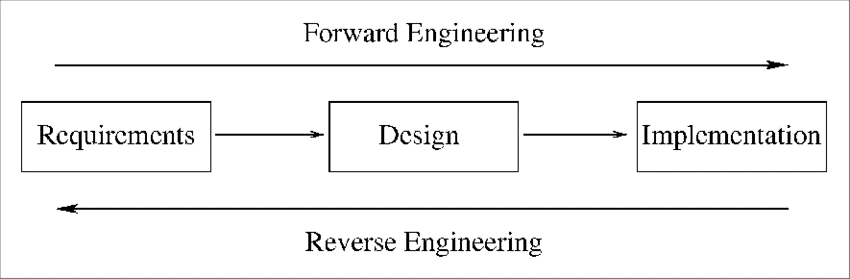

It was clear from our meeting that Dr. Raman has a vision. She wants to challenge standard approaches to biology, combine them with technology, and build biological robots that respond to their environment and perform tasks beyond the capabilities of typical robots. What is unique about Dr. Raman’s approach is that she utilizes forward engineering instead of reverse engineering. In medicine and engineering, scientists often observe biological systems to “reverse” the engineering design process and better understand how systems work. On the other hand, Dr. Raman wants to build on existing biological systems rather than just create something that looks and acts similarly.

With the help of her colleagues, Dr. Raman engineered a biohybrid robot (a robot with biological components) that moves with mouse skeletal muscle, which they developed by culturing stem cells in sugar water that eventually sprouted into muscle tissue. I wondered if the next step might be to use other bodily tissues like connective tissue, cartilage, or nervous tissue in future models—if so, you could make these robots incredibly advanced! She explained that her team is highly interested in integrating neural control and sensory feedback, allowing biohybrid robots to assess and respond to their environment. For example, if the robot’s muscle senses stretching, it could generate more force in response. However, since her team makes tissues from scratch, this presents a difficult challenge, and it is even tougher to make the cells communicate.

With the help of her colleagues, Dr. Raman engineered a biohybrid robot (a robot with biological components) that moves with mouse skeletal muscle, which they developed by culturing stem cells in sugar water that eventually sprouted into muscle tissue. I wondered if the next step might be to use other bodily tissues like connective tissue, cartilage, or nervous tissue in future models—if so, you could make these robots incredibly advanced! She explained that her team is highly interested in integrating neural control and sensory feedback, allowing biohybrid robots to assess and respond to their environment. For example, if the robot’s muscle senses stretching, it could generate more force in response. However, since her team makes tissues from scratch, this presents a difficult challenge, and it is even tougher to make the cells communicate.

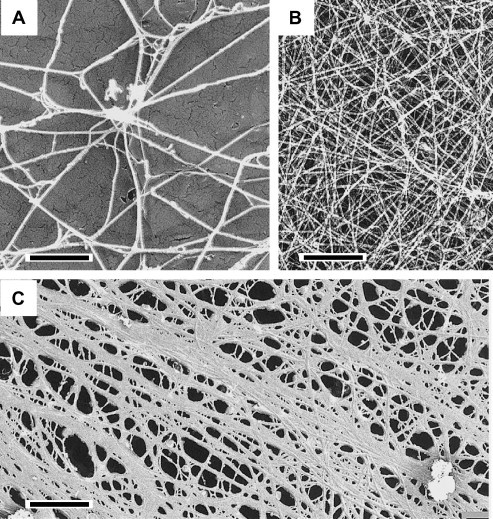

Since Dr. Raman’s team uses living tissue, I was also curious about biohybrid robots’ lifespans. I wanted to learn more about their potential sustainability, which is still unclear. Some died after a month, but others lasted an entire year. Scientists damage muscle cells when they research them. In response, cells break down their cell matrix, which is their support system. This cell behavior is expected in humans because their bodies can replace damaged cell matrices with healthy ones. However, since there is no replacement matrix in biohybrid robots, they eliminate their physical support. With more research, Dr. Raman and her team could use this behavior to their advantage to control their lifespans. If a patient has fully recovered from an illness, it could essentially self-destruct when it is no longer helpful. However, there is still more work to do.

It is important to remember that products take years to reach the public in biomedical sciences, so we consider anything with five years or less of work remaining to be “almost finished.” Even though there is still so much research left to do, Dr. Raman believes that her biohybrid robots are close to being ready for some applications, like disease modeling, which could reach the public within the next ten years. Not only could disease-modeling robots change the world of medicine, but also they have the potential to expedite the process of FDA drug testing to save countless lives. However, fully untethered robots for invasive surgeries could take more than 20 years to reach the public. Still, Dr. Raman states that each year brings successful milestones that get them closer to a finished product.

It is important to remember that products take years to reach the public in biomedical sciences, so we consider anything with five years or less of work remaining to be “almost finished.” Even though there is still so much research left to do, Dr. Raman believes that her biohybrid robots are close to being ready for some applications, like disease modeling, which could reach the public within the next ten years. Not only could disease-modeling robots change the world of medicine, but also they have the potential to expedite the process of FDA drug testing to save countless lives. However, fully untethered robots for invasive surgeries could take more than 20 years to reach the public. Still, Dr. Raman states that each year brings successful milestones that get them closer to a finished product.

We also discussed where current robotic research falls short. Dr. Raman believes that regular robots work well for some fields but not others. Skeletal muscle converts chemical energy to mechanical energy using sugar as fuel instead of batteries, eliminating toxic byproducts and making them much safer for surgical procedures. Additionally, biohybrid robots adapt well. Consider robotics for medicine. People respond to diseases differently, but mechanical robots will provide the same treatment for each patient. A biohybrid robot has the potential to read and adjust its technique for each person. Therefore, while a mechanical robot might suit repetitive tasks like car manufacturing, Dr. Raman’s robots are dynamic and can provide personalized medicine.

Once we finished talking about her fascinating work, Dr. Raman shared some challenges faced throughout her career journey. I was particularly interested in learning about her experiences as a STEM professional. She recalled moving around a lot as a child, from Kenya to India and eventually to the United States. As a result, she learned to adapt to different experiences and quickly adjust to new situations. Therefore, when it came to being a woman in STEM, she shared that she felt used to being the odd one out and knew how to deal with it. Dr. Raman explained that her elders sometimes tried to discourage her by saying there were no famous female scientists, but she overcame this since her mom and dad were engineers.

Additionally, she described occasionally experiencing “imposter syndrome” or believing she is not good enough for her role because society views women in STEM skeptically, even though she is more than qualified. Dr. Raman credits her mother, an engineer, for showing her that women do belong in STEM. As a male biomedical engineering student, this was something I never had to consider. Still, I need to internalize this as I start to work and network in biomedical engineering and become a good colleague.

Dr. Raman is an incredible example of educational persistence, and it was helpful to talk with her because I have similar career aspirations. One day, I hope to obtain a Ph.D. and work in a biomedical research environment. I can now apply her life lessons and experiences to meet my goals in the future and contribute positively to the STEM community. Dr. Raman’s work is precisely the kind of thinking needed to change the world.

Image Captions:

Figure 1 Dr. Raman at Work

Figure 2: Reverse and Forward Engineering (https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Relations-of-reverse-and-forward-engineering-to-the-software-development-process_fig1_270960229)

Figure 3: Cell Matrix (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1046202308000297)

Nathan Green is a summer intern for the Programs Team at the Connecticut Science Center. He is currently studying Biomedical Engineering at the University of Hartford. He one day hopes to contribute to NASA’s mission to colonize Mars with the help of biotechnology or to advance research in tissue engineering. Prior to joining the Science Center, Nathan worked in childcare.